And after all the violence and double talk

There’s just a song in the trouble and the strife

You do the walk, you do the walk of life

Lyrics to a popular song

Having cancer can feel like being in prison, especially when you’re undergoing surgery, chemotherapy, or any other number of aggressive treatments. You watch your family, close friends, and everyone around you continue to live normal lives, as your own existence becomes increasingly constrained. This was my personal experience when my ovarian cancer caused me to spend seven weeks in the hospital and when I underwent five rounds of chemotherapy. I was left exhausted, miserable and temporarily unable to engage in an active or fulfilling life.

Now that I’ve achieved remission I’ve gratefully resumed doing many of the things that I took for granted before my diagnosis, most of all I appreciate the freedom of being outside and going for long walks. It’s been a relatively mild winter in southern Alberta and this weather has been perfect for maintaining my daily walking routine. I usually prefer to walk alone and in the morning, this practice seems to help me achieve the maximum emotional and psychological benefits. Of course there are particular occasions when walking with others is the best choice, I’ve proudly marched with close to 400 people in the 5 kilometre Ovarian Cancer Canada Walk of Hope. Each year this Canada-wide event raises about 2 million dollars for research, awareness and support.

Study after study has extolled walking as a simple, inexpensive exercise with incredible health benefits. From a cancer patient’s perspective, walking regularly has been proven to strengthen the body and ease the mind. Several recent studies suggest that higher levels of physical activity are associated with a reduced risk of the cancer coming back, and longer survival after a cancer diagnosis. Here are some other recent findings regarding the advantages of exercise, specifically walking:

- A daily one hour walk can cut your risk of obesity in half.

- Thirty to 60 minutes of exercise most days of the week drastically lowers your risk of heart disease.

- Logging 3500 steps a day lowers your risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 29 per cent.

- Walking for just two hours a week can lower your risk of having a stroke by 30 per cent.

- Walking for 30 minutes a day can reduce symptoms of depression by

36 per cent.

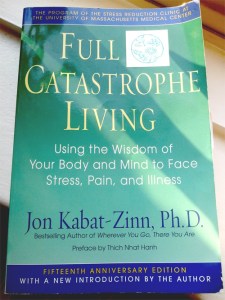

A number of experts advocate walking as a form of meditation to help relieve stress or anxiety. For instance, Jon Kabat-Zinn’s classic Full Catastrophe Living includes an entire chapter on walking meditation. Many people with chronic illnesses, including cancer, find that they enjoy walking more when they intentionally practice being aware of their breathing and of their feet and legs with every step. There are numerous ways in which walking can help you gain greater self-awareness, as I stride down a sidewalk or path I will often utilize my senses to make me more conscious of the moment. One day I might concentrate on my sense of touch and notice the wind in my hair or the warmth of the sun on my face. The next time I’m out for a walk I’ll focus on my sense of smell and how the delicious aroma of our neighbourhood bakery is apparent when you come within about half a block of the bread and pastries.

Finally, there is growing evidence that walking stimulates our creativity and though processes. We can thank Steve Jobs for the business community’s blossoming love affair with the mobile meeting. “Taking a long walk was his preferred way to have a serious conversation,” observed Walter Isaacson in his bestselling biography of Apple’s co-founder. Some studies have actually indicated a link between walking and memory. One study found that walking 40 minutes three times a week might protect the brain region associated with planning and memory. This is significant for cancer patients, since a fair number of us report issues with recall and comprehension that are related to chemotherapy or other treatments.