In my opinion living with cancer is one of the most difficult and brutal things that any person will ever have to face, to have cancer is to live moment by moment and it’s not always easy for us to look toward the future. Still, I feel I’m in a better situation than many because I’ve been in remission for eleven years. My long remission and the fact that my city, Calgary, Alberta, intends to open a new state-of-the-art cancer centre this year has me facing the New Year with hope and optimism.

The Arthur J.E. Child Comprehensive Cancer Centre

At some point in 2024 I’ll witness the grand opening of Canada’s largest and newest comprehensive cancer centre! I experienced how desperately we needed a new cancer centre when I was going through treatment. Our city’s existing Tom Baker Centre has been serving men and women diagnosed with cancer for approximately two generations now; it opened its doors over 40 years ago in the early 1980s. At the time, Albertan’s marveled at the spacious and innovative new facility. The building had been meticulously designed to provide cancer care for Calgary’s population and the rest of southern Alberta. Although the Baker Centre’s first doctors once pondered how exactly they’d fill all the new space available to them, I saw the present day oncologists, nurses and technicians grapple with cramped offices, crowded reception areas and patients lining the hallways waiting for treatment.

When it opens later this year, it’s promised that the new Arthur J.E. Child Comprehensive Cancer Centre will engage patients as the focus of a multidisciplinary health system, we will have access to comprehensive cancer care services in a state-of-the-art facility. In fact, the extensive scope and integration of cancer care services at Calgary’s new hospital will make it one of the most comprehensive cancer centres in the world. Operationally, the Arthur Child will include both inpatient and outpatient services. Services based on clinical priorities are to include:

- more than 100 patient exam rooms

- 160 inpatient unit beds

- more than 100 chemotherapy chairs

- increased space for clinical trials

- 12 radiation vaults, with three more shelled in for future growth

- new on-site underground parking with 1,650 stalls.

- numerous outpatient cancer clinics

- clinical and operational support services and research laboratories

Important Oncology Breakthroughs

There’s no doubt that COVID-19 caused a huge backlog in cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, there is still plenty of positive news. Despite the recent global pandemic, medical advances are still accelerating the battle against cancer. Here are a few of the exciting recent developments in the field of oncology!

The seven-minute cancer treatment

The National Health Service (NHS) in England is to be the first in the world to make use of a cancer treatment injection. It takes just seven minutes to administer, rather than the current time of up to an hour to have the same drug via intravenous infusion. This will not only speed up the treatment process for patients, but also free up time for medical professionals. The drug, Atezolizumab or Tecentriq, treats cancers including lung and breast, and it’s expected most of the 3,600 NHS patients in England currently receiving it intravenously will now switch to the new injection.

Precision oncology

Precision oncology, defined as molecular profiling of tumors to identify targetable alterations, is rapidly developing and has entered the mainstream of clinical practice. Precision oncology involves studying the genetic makeup and molecular characteristics of cancer tumours in individual patients. The precision oncology approach identifies changes in cells that might be causing the cancer to grow and spread. Personalized treatments can then be developed. Because precision oncology treatments are targeted – as opposed to general treatments like chemotherapy – it can mean less harm to healthy cells and fewer side effects as a result.

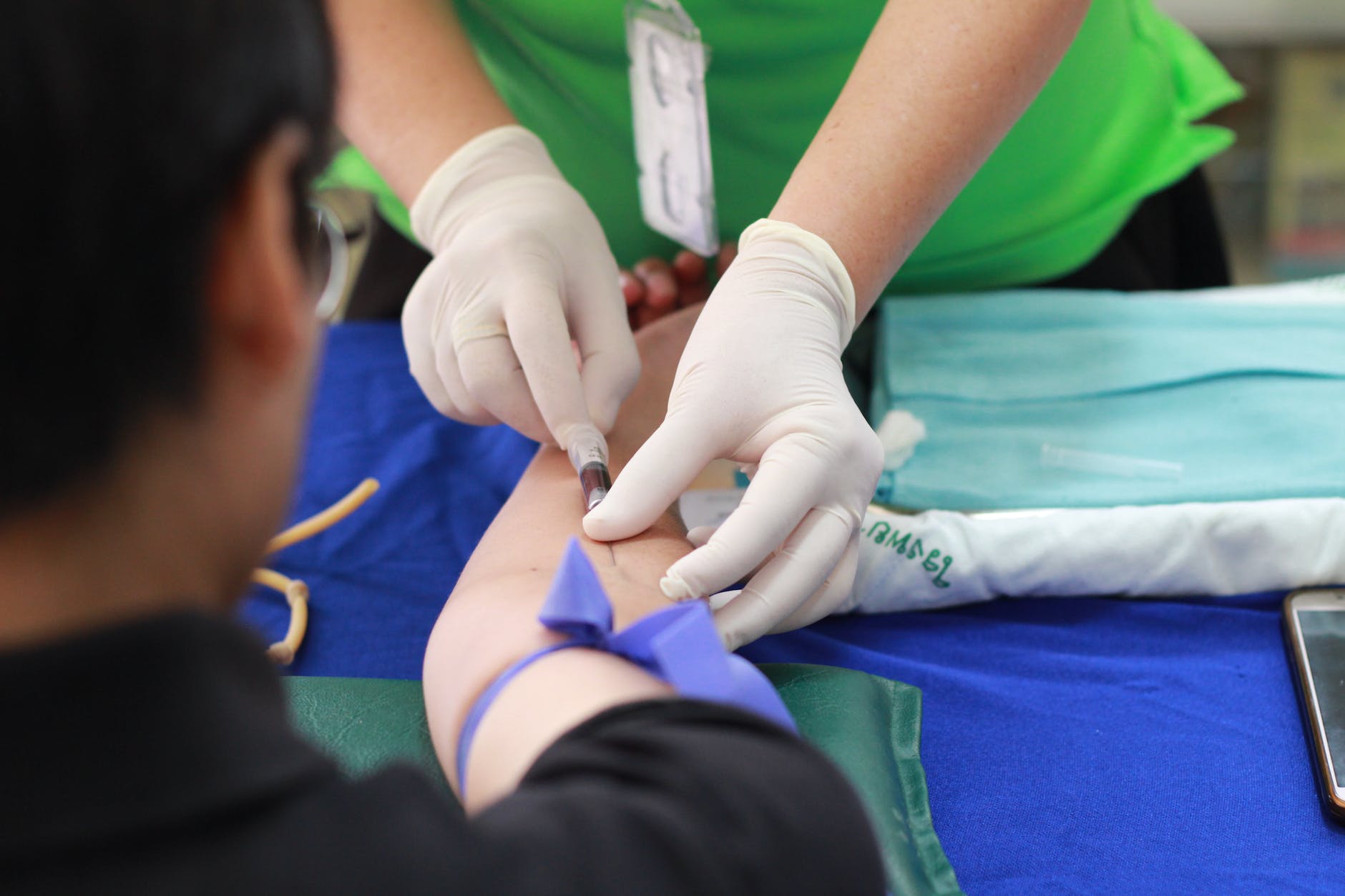

Liquid and synthetic biopsies

Biopsies are the main way doctors diagnose cancer – but the process is invasive and involves removing a section of tissue from the body, sometimes surgically, so it can be examined in a laboratory. Liquid biopsies are an easier and less invasive solution where blood samples can be tested for signs of cancer. Synthetic biopsies are another innovation that can force cancer cells to reveal themselves during the earliest stages of the disease.

Car-T-cell therapy

A treatment that makes immune cells hunt down and kill cancer cells was recently declared a success for leukaemia patients. The treatment, called CAR-T-cell therapy, involves removing and genetically altering immune cells, called T cells, from cancer patients. The altered cells then produce proteins called chimeric antigen receptors (CARs). These recognize and can destroy cancer cells. In the journal Nature, scientists at the University of Pennsylvania announced thattwo of the first people treated with Car-T-cell therapy were still in remission 12 years on.